by Nancy Christofferson

STONEWALL — If waging “wars” in Trinidad and Colfax counties were not enough controversy for our small world out in Spanish Peaks country, along came the Stonewall War in 1888.

The Stonewall Valley on the upper Purgatory River was settled permanently around 1870 by homesteaders. These included Luis Torres, Juan Gutierrez, Richard D. Russell, and Frank B. Chaplin. Already living in the area was a squatter and old fur trapper, J.A. Weston.

More homesteaders followed and by 1876 there were enough families to warrant the construction of a school, church and, unfortunately, a cemetery. By 1890, nine of these settlers had received their final homestead papers in the form of deeds patented by the U.S. Government. Legal deeds.

Tying together some of the incidences in Las Animas and Colfax counties in the previous years was Richard Russell. Russell had been a soldier at Fort Union who accompanied Colonel Andrew Alexander in his battles against Ute Chief Kaniache, defeating him in Long’s Canyon west of Trinidad and later on the prairie north of Trinidad.

Russell had married at the fort in 1865 and he and his wife Marion lived next door to Kit Carson, one-time agent for the Utes and Apaches. Once Richard left the military, he and a friend opened a store in Tecolote in 1867. The friend absconded with their money. One of their best customers, later a friend, had been one Lucien Maxwell. Another was a young German named George Storz.

In 1871 Richard, who had sold out what stock he had, was moving his family to the San Luis Valley when he chanced upon a woman north of Trinidad who convinced him to go instead to St. John’s Valley, nearly 40 miles upriver. He did.

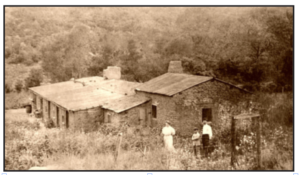

The Russells are credited with renaming St. John to Stonewall Valley. They built a small cabin just north of the great stone wall and beside an ancient trail used by Utes and Apaches traveling to and from their agency at Maxwell’s mill on the Cimarron. Later the family moved to the south side of the wall, where it was warmer. Russell again opened a store, and became first post master of the community when it officially became Stonewall in 1878.

The settlers raised cattle, wheat, hay and potatoes. Their orchards yielded fresh fruit, their gardens fresh vegetables to sell. Their dairy cows provided large quantities of butter freighted as far as Fort Lyon on the Arkansas. Other products were sold or traded in Taos or Santa Fe where chiles and onions were obtained. Life was good.

Well, at least life was good… had there been no Maxwell Land Grant and Railway Company.

In 1887, that company, then owned by a Dutch syndicate, had apparently exaggerated its purchase agreement of the original Maxwell Grant, supposedly limited by law to 96,000 acres, by claiming no less than 1,714,764.94 acres, more than 250,000 of them in the Purgatory Valley of Colorado. Maxwell himself apparently considered his grant’s northern border to be the Canadian or Red River. His successors claimed it was the Purgatory, and the U.S. Congress that very year confirmed the company’s claim.

The company began informing settlers they were not homesteaders, but squatters and transients. It offered to allow them to remain on their properties, with their improvements and livestock, if they agreed to sign over ownership to the company and pay rent. Some did, but many saw this as a fraudulent land grab. They sued, but the wheels of justice etc.

In March 1888 Richard Russell faced a jury in Trinidad defending himself against company claims of theft of cattle and timber. He was found not guilty. The company reacted by informing the settlers they could keep their cattle but would have to pay pasture rent of 75 cents per head, per year. The situation worsened daily.

In July 1888, the Dutch owners began sending eviction notices to all “squatters” on its land. In response, the Stonewall Alliance No. 1 was formed. Russell was elected vice-president. The new group was based on the existing Colfax County alliance that was modeled after, but not identical to, alliances formed elsewhere to defy foreign ownership and huge landholdings, if not land grants per se.

Assisting the alliance and speaking out for the anti-granters was our old friend O.P. McMains, the self-styled “Agent for the Settlers” in Colfax County.

To compound difficulties was the formation of the Stonewall Summer Resort syndicate, which obtained 5,220 acres from the grant company. This included the Stonewall hotel, a two story frame affair with 16 rooms.

The villain of this piece was the grant company’s general manager, M.P. Pels. Pels had appealed to federal authorities as well as the governors of both New Mexico and Colorado for military assistance to deal with the trouble makers. He received no assurances but continued to bear pressure on the settlers to either pay up or move on. The settlers only became more belligerent.

Soon employees preparing the new summer resort began reporting confrontations with the settlers, as well as threats. Several were convinced to move on themselves, and reported these “disturbances” to the county sheriff who sent six deputies to Stonewall to prevent trouble. He also deputized no fewer than 35 men, who were apparently so gung ho they left for Stonewall immediately.

Around August 24, Russell and others had dispersed throughout the country, warning settlers of the presence of the deputies and possible reinforcements. The deputies meanwhile made themselves comfy in the hotel.

On August 25, some 50 settlers, all armed and masked, converged on the hotel. A large contingent of riders appeared, led by none other than O.P. McMains. They were from New Mexico, and brought the number of settlers to about 200.

Russell, representing the settlers, with several others, demanded the deputies surrender. They refused. The settlers surrounded the hotel. Someone fired his weapon.

When the shot was fired, Richard Russell, standing by the hotel door, took the only shelter available, between the door and a window. As gunfire continued from both sides, he fell to the ground.

Bullets were still flying an hour or more later when a flag of truce appeared from the hotel. The employees wanted to leave, and firing ceased. During the lull, the fallen Russell and the body of 18-year-old Rafael Valero, a settler, were removed.

Late that afternoon a rider reached Trinidad with news of the bloodshed. Seems those 35 deputies had dwindled to zero, and no one else was volunteering for a posse.

Finally, two of the county commissioners, including Richens L. “Uncle Dick” Wootton, declared they would go to restore order.

The settlers that night had burned a barn across the road from the hotel, which illuminated the front of the hotel and left the rear in shadow. The deputies escaped out the back and disappeared.

Early on August 26, the commissioners arrived by buggy and entered the hotel. Empty. As they were dealing with this surprise, a large group arrived from La Veta with wagon loads of supplies. Now there were 400 or 500 armed gunmen.

Russell died of his injuries the next day, leaving his wife and eight children. It was found he had been shot from above, by the deputies. The settlers burned down the hotel in revenge.

Still, there was no response from any government entities. However, public opinion had turned sharply in favor of the settlers protecting their properties and families.

McMains was blamed for the whole sorry affair and a warrant for murder was issued. He merely went back to New Mexico, where the governor refused to sign extradition papers.

At the conclusion of the Stonewall War, nothing had really changed. Two settlers were dead. Six deputies were charged with murder. The company continued to evict settlers.

The Russell family was deeply impacted by its loss – Marion continued to insist her husband was murdered while he was carrying his white flag of truce. She finally settled with the company by signing over a part of her ranch.

Peace returned to the beautiful valley. Many members of the original families have made it their home to this day.