by Nancy Christofferson

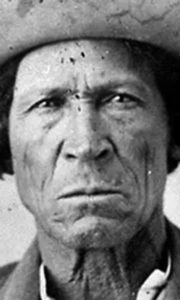

HUERFANO — After most of the residents of southern Colorado near Pueblo abandoned their homes and fields after the Christmas massacre at Fort Pueblo in 1854, the valleys were sadly empty of humanity. Charley Autobees, however, refused to give up.

HUERFANO — After most of the residents of southern Colorado near Pueblo abandoned their homes and fields after the Christmas massacre at Fort Pueblo in 1854, the valleys were sadly empty of humanity. Charley Autobees, however, refused to give up.

His trapper and trader friends returned to what is now northern New Mexico. Remember – Huerfano County as we know it was located in New Mexico Territory, as it had been since the treaty ending the Mexican-American War in 1846. His friend and benefactor, Ceran St. Vrain, no doubt wished him the very best in attracting those former residents who had fled to come back to the Huerfano River, and to discover new settlers as well.

In late 1855 Charley built himself a large adobe placita on the west side of the river where he had been on the east side previously. This new home was a part of a walled quadrangle with two gates. Soon some of the earlier residents, owners and employees, began to return, including William Kroenig, old friend Charlefoux and his slightly-demented cook, Chiquito Trujillo.

That year he grew potatoes, corn, beets and rutabagas on the irrigated fields, along with the more delicate vegetables planted and nurtured by the women of the settlement for their own family use. Sycamore was still with him, along with her brother with his wife and children, her two sons, servants, and even a newly adopted Arapaho daughter, possibly kin to Sycamore.

In 1856 Charley was farming and selling or trading his crops regularly as far away as the Platte River. One day when he was hauling a wagonload to trade with the Arapahoes, his little family accompanied him. Near Pueblo, on the north side of the Arkansas, Sycamore spotted horsemen on top of the bluffs. They were identified as warriors. He unhitched the team, tied them, fortified the wagon bed with sacks of flour and corn for the protection of his passengers, and was ready to return fire when the horsemen revealed themselves as “Kaneatche’s” Utes. Sycamore grabbed a rifle (belonging to the son of crazy Chiquito who had hidden under the wagon and never fired a shot). She joined the fray and, when Charley was hit by a bullet in the arm, she also loaded his rifle so he could continued shooting. After many hours of flying bullets, the Utes left with “seven empty saddles” according to Charley. His only loss was of two oxen. Apparently, he told this story for years to come, portraying Sycamore as the hero of the day.

In 1857 Serafina Avila Autobees and her children joined Charley in his little village. Sycamore stayed with him until her death in 1864.

Charley didn’t only trade with the Indian nations and the rare settlers in the area, but also routinely took supplies all the way to Fort Union in New Mexico.

He also made trips to Bents’ New Fort, 80 miles downriver at Big Timbers. The original Bent’s fort had been abandoned and partially destroyed, leaving travelers to remark on the old trail from the fort to Pueblo as “barely visible” due to lack of use.

Of course the Autobees family had many adventures, failures and successes in their lonely world. An almost tragedy occurred in a May 1858 blizzard which killed many of the horses and other livestock and scattered the survivors. Crops were killed and some soldiers camping near the placita were frozen to death.

In 1859 traffic picked up on the trail passing Charley’s place when immigrants heading for California traveled through, including a party washed to the south shore of the Arkansas. One of these wrote in his journal of the fine corn and pumpkins, garden truck and flour at Autobees’ place. Charley himself went into the ferry business to assist river crossings.

That winter Charley found new markets to the north as gold miners settled into their new community on the Platte at later Denver, but the next year brought the beginning of the Civil War and traffic dropped off. Charley threw himself into his ferry business and when Colorado’s first legislature was established, took out the necessary permits for the ferry business.

In February 1861, Colorado Territory was established, and Charley finally lived in the county named Huerfano. The county boundary ran from the mountain peaks on the west to the new Kansas line on the east, and from the Arkansas south to the border with New Mexico Territory. This vast land contained, by estimation, some former New Mexican citizens and around 50 former Americans. Another statistic offered was that Huerfano’s population density was one person to every 150 square miles.

The new territory elected William Gilpin its governor. Gilpin was an old associate of many pioneers, having come west on the Santa Fe Trail and befriended numerous trappers and explorers through the years. It was he who appointed Charles Autobees county commissioner, along with his neighbors to the south, but also living along the Huerfano River, Joseph B. Doyle and Norton W. Welton. A former neighbor, George Simpson, was made clerk and recorder. Huerfano was authorized November 1, 186l, at which time these officers became official.

The county seat of the new Huerfano County was Autobees. In February 1862 a post office named Huerfano was established in the vicinity. Otherwise Pueblo had the nearest postal service and had since 1860. In 1866, Huerfano was split, so Las Animas County was created and other bits and pieces of real estate went to other counties. The Huerfano post office was suddenly in Pueblo County, and the name was later changed to Undercliffe.

In Huerfano County, “Autobis town” was Precinct One with the official polls presumably in Charley’s house. The first meeting of the county commissioners was on November 21 at which time a real election was scheduled for December 2. Charley was duly elected to his post, and also as a Justice of the Peace – not bad for an illiterate. Charlie must have considered Colorado to be the land of promise.

As a justice, Charlie was charged with administering oaths of office as well as the oaths for witnesses at trials. He memorized the words of the standard oaths, sort of, and solemnized the procedures with a “so help me by God” instead of “so help me God”. His last meeting as commissioner was February 10, 1863. He never again sought office.

In 1861 Charley was robbed by Comanches who took seven of the best horses in the area, valued at $150 each at a time when a serviceable riding horse cost ten bucks. The Indian agent of the day, Charley’s neighbor across the Huerfano, Albert Gallatin Boone, extracted a promise from the Comanche head man the horses would be returned but only one ever was – a heavy loss.

In March 1864 Charley was given a franchise for his ferry until a bridge could be built. High water a month later put him out of business when the Arkansas flooded so seriously the banks were taken, along with the farms, settlements, fields, livestock, and even the burial place for the Fort Pueblo massacre victims.

About the same time, attacks by Cheyennes and Arapahoes kept the soldiers at Fort Wise, near the former Bent’s New Fort downriver, busy.

In 1867, William Craig, agent for Ceran St. Vrain, made a deal to lease land for 15 years to the Army below the mouth of the St. Charles River, “northwest to Charles Autobees” place and the Huerfano River, then back along the Arkansas to the St. Charles. It was named Fort Reynolds and troops arrived that summer. It was said the fort eventually occupied 23 square miles surrounding a parade ground where about 30 adobe and frame buildings went up.

The post did not last anywhere near 15 years but just five. In 1872 it was abandoned, possibly because of the frequent flooding. Instead of reverting to the ownership of the old land grant, however, a land grab began. In fact, the government insisted the land had been purchased, not leased, so Charley’s acres used by the Army, sort of left with the Army. He was first denied ownership of that portion, then the entire parcel given to him by St. Vrain nearly 20 years before, and on which he had made his home, and those of his family and of his friends all that time. He hired lawyers who collected testimonies from other early settlers, including the Bent family and Kit Carson, to prove his residency and improvement of the land since 1853, to no avail.

He was, at least, permitted to stay in his plaza and farm. In his 60’s, he had nothing to show for his industry and public service for two decades. He was dead broke, and bereft.

Charley got a raw deal, but he somehow lived with it, though he died in 1882, landless and moneyless. As time went on his very existence was forgotten or ignored.

He could be considered the original orphan of Orphan County. Charley is seldom lauded or credited for his pioneer residency, in fact, Charley is seldom remembered at all, which is why I always say, he ain’t famous, but he Auto Be.